How about understanding Communicative Competence for Applied Linguistics?

Read the text below and do the memory game in order to check your knowledge. Enjoy it!

On Defining Communicative Competence (H. Douglas Brown)

The term ‘communicative competence’ was coined by Dell Hymes (1967, 1972), a sociolinguist who was convinced that Chomsky’s (1965) notion of competence was too limited. Chomsky’s ‘rule-governed creativity’ that so aptly describes a child’s mushrooming grammar at the age of 3 or 4 did not, according to Hymes , account sufficiently for the social and functional rules of language. Communicative competence, then, is that aspect of our competence the enables us to convey and interpret messages and to negotiate meanings interpersonally within specific contexts. Savignon (1983:9) notes that “communicative competence is relative, not absolute, and depends on the cooperation of all the participants involved.” It is not so much an interpersonal construct as we saw in Chomsky’s early writings, but rather, a dynamic, interpersonal construct that can only be examined by means of the overt performance of two or more individuals in the process of negotiating meaning.

In the 1970s, research on communicative competence distinguished between linguistic and communicative competence (Hymes 1967, Paulston 1974) to highlight the difference between knowledge “about” language rules and forms and knowledge that enables a person to communicate functionally and interactively. In a similar vein, James Cummins (1979, 1980) proposed a distinction between cognitive/academic language proficiency (CALP) and basic interpersonal communicative/academic skills (BICS). CALP is that dimension of proficiency in which the learner manipulates or reflects upon the surface features of language outside the immediate interpersonal context. It is what learners often use in classroom exercises and tests which focus on form. BICS, on the other hand, is the communicative capacity that all children require in order to be able to function in daily interpersonal exchanges. Cummins ( 1981) later modified his notion of CALP and BICS in the form of context-reduced and context-embedded communication, where the former resembles CALP and the later BICS, but with the added dimension of considering the context in which language is used. A good share of classroom , school-oriented language is context-reduced, while face-to-face communication with people is context-embedded. By referring to the context of our use of language, then, the distinction becomes more feasible to operationalize.

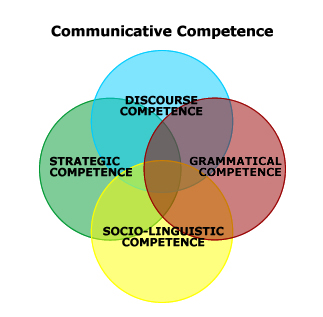

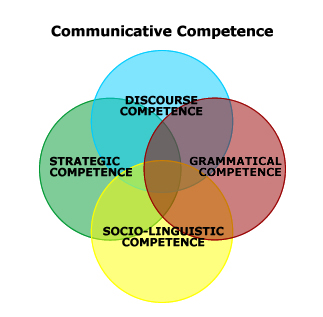

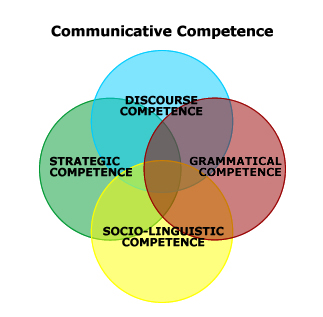

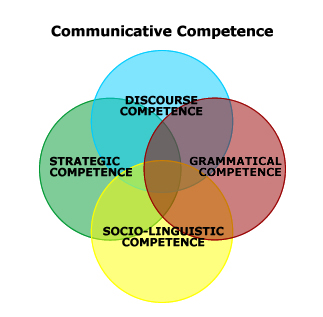

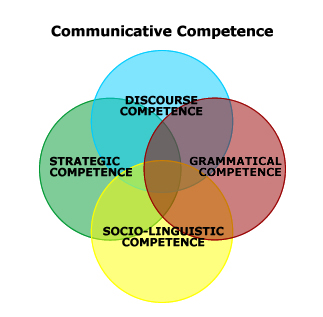

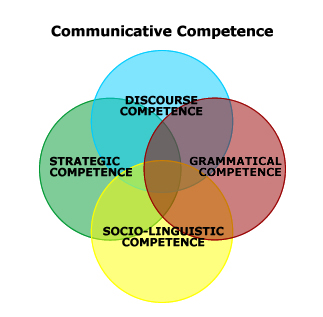

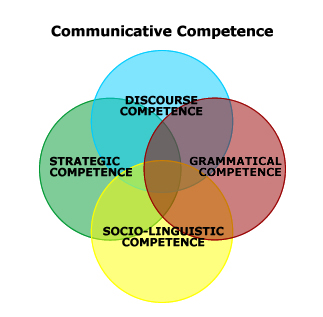

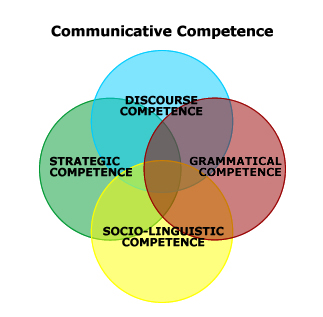

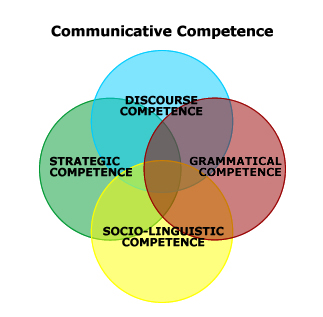

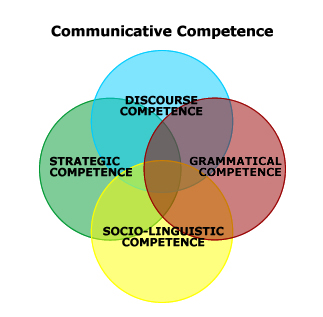

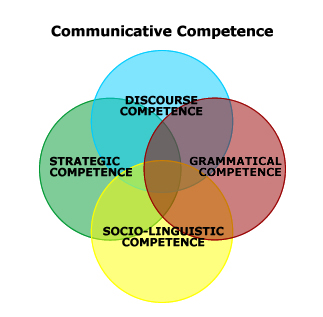

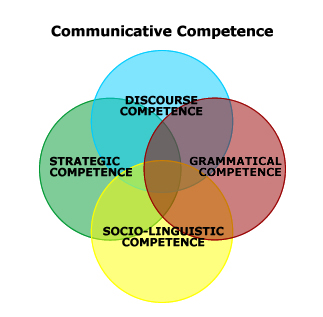

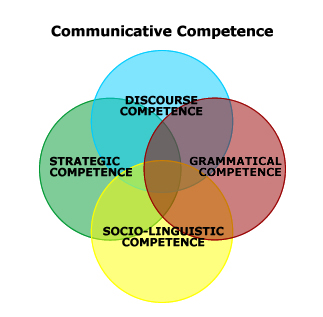

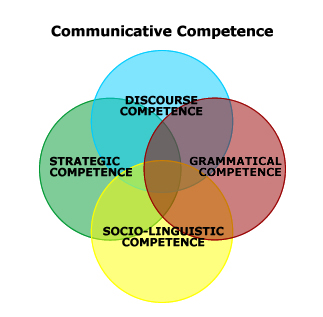

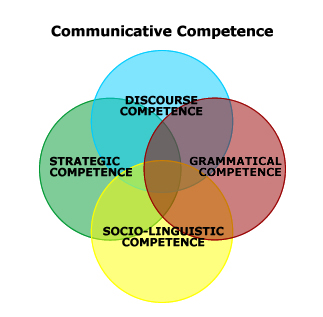

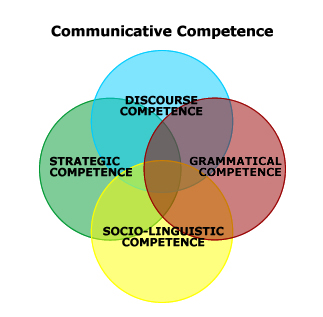

Seminal work on defining communicative competence was carried out by Michael Canale and Merrill Swain (1980), now the reference point for virtually all discussions of communicative competence vis-à-vis second language teaching. In canale and Swain’s (1980) and later Canale’s (1983) definition, four different components, or subcategories reflect the use of the linguistic system itself. Grammatical Competence is that aspect of communicative competence that encompasses “knowledge of lexical items and of rules of morphology, syntax, sentencegrammar semantics, and phonology” (Canale and Swain 1980:29). It is the competence that we associate with mastering the linguistic code of a language, the “linguistic” competence of Hymes and Paulston, referred to above.

The second subcategory is discourse competence, the complement of grammatical competence in many ways. It is the ability we have to connect sentences in stretches of discourse and to form a meaningful whole out of a series of utterances. Discourse means everything form simple spoken conversations to lengthy written texts (articles, books, and the like). While grammatical competence focus on sentence-level grammar, discourse competence is concerned with intersentential relationships.

The last two subcategories define the more functional aspects of communication. Sociolinguistic competence is the knowledge of the sociocultural rules of language and of discourse. This type of competence “requires an understanding of the context in which language is used : the roles of the participants, the information they share, and the function of the interaction. Only in a full context of this kind can judgments be made on the appropriateness of a particular utterance “ (Savignon 1983:37).

The fourth subcategory is strategic competence, a construct that is exceedingly complex. Canale and swain (1980:30) described strategic competence as “the verbal and nonverbal communication strategies that may be called into action to compensate for breakdowns in communication due to performance variables or due to insufficient competence.” Savignon (1983:40) paraphrases this as “the strategies one uses to compensate for imperfect knowledge of rules – or limiting factors of their application such as fatigue, distraction, and inattention.” In short, it is the competence underlying our ability to make repairs , to cope with imperfect knowledge, and to sustain communication through ‘paraphrase, circumlocution, repetition, hesitation, avoidance, and guessing, as well as shifts in register and style” (Savignon 1983:40-41). Strategic competence occupies a special place in an understanding of communication. Actually, definitions of strategic competence that are limited to the notion of “competence strategies” fall short of encompassing the full spectrum of the construct. All communication strategies arise of a person’s strategic competence. In fact, strategic competence is the way we manipulate language in order to meet communicative goals. An eloquent speaker possesses and uses a sophisticated strategic competence. A salesman utilizes certain strategies of communication to make a product seem irresistible. A friend persuades you to do something extraordinary because she or he has mustered communicative strategies for the occasion.